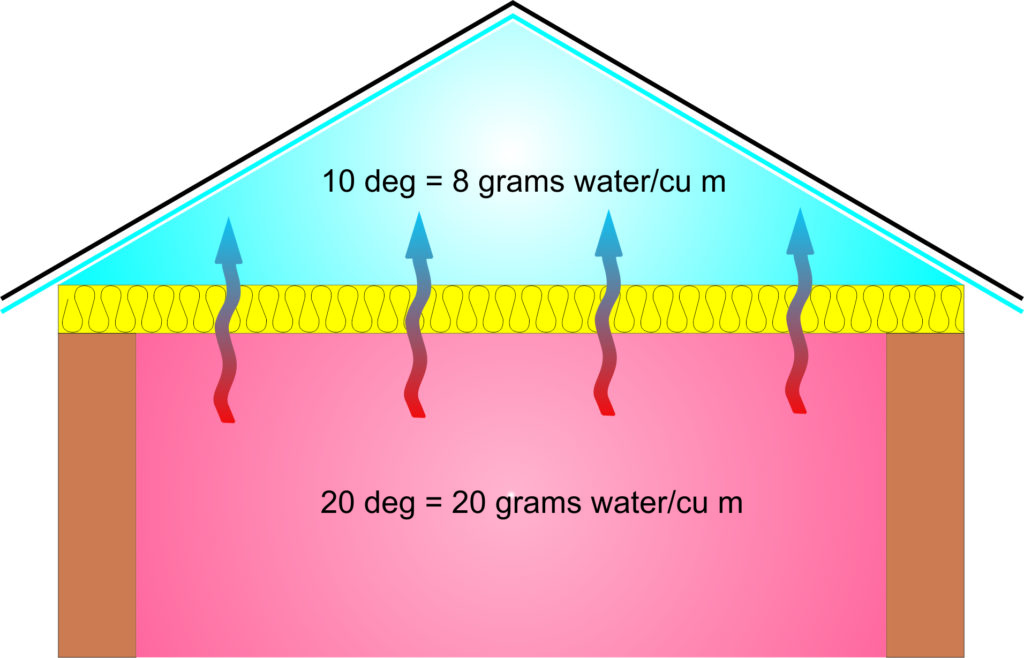

As we strive to improve the energy efficiency of our homes, greater levels of thermal insulation and air tightness reduce the average temperatures within the roof structure. Warm moist air, generated within the living spaces, can find its way through the ceiling into the cold roof space. Controlling condensation within our buildings remains one of our key goals to ensure we live and work comfortably, healthily and to prevent damage to the building fabric.

The ability of air to hold moisture reduces as it cools, and it will then deposit the moisture onto cold surfaces in the form of condensation. For example, in a two-storey house with a floor plan of 100 m2, there is around 420 cu metres of air, which, at 20 degrees, could potentially hold up to 8.4 litres of water vapour. If this warm air passes through the ceiling into the roof space and cools down to 10 degrees, it can then only hold 3.4 litres of water vapour. This means that 5 litres of water will be deposited somewhere if it is not allowed to escape from the roof space. It may not be as dramatic as that in practice, but it illustrates the potential risks.

The development of vapour-permeable and air-permeable roofing underlays has been greatly beneficial in helping to prevent harmful levels of condensation from building up in the roofspace. However, it is important to use these products correctly, in accordance with the guidance given in BS 5250 and with the information contained in the underlay manufacturer’s accreditation certificate.

Essentially, in simple terms, there are two ways we can control the risk of condensation build up in the roofspace, ie, we either prevent water vapour from reaching the loft space in the first place, or we remove it once it gets there before it has chance to build up to harmful levels.

To prevent the water vapour passing from the living space into the cold roof space, it is necessary to install effective vapour barriers. It is difficult, if not impossible to construct a totally air and vapour-tight ceiling, so British Standard BS 9250 gives guidance on minimising air leakage through junctions and penetrations such as light fittings, loft hatches etc to create a ‘continuous’ ceiling. We now have well-documented methods to achieve this in new buildings, though it is generally more difficult in existing buildings. Greater energy efficiency is achieved, and the risk of condensation reduced if we prevent air leakage through the ceiling. However, where this is not practical, we must use adequate ventilation to remove the water vapour from the roof space.

BS 5250 sets out the minimum requirements for roofspace ventilation. For example, in the average house with a cold loft, there should be a minimum of a 7mm continuous ventilation gap at eaves when using a vapour permeable underlay with a normal, or ‘discontinuous’ ceiling. With all the benefits of dry fix systems well documented, it makes perfect sense to supplement eaves ventilation with high-level ventilation using a dry ridge system. Although eaves to eaves ventilation works well in theory, it relies on external air movement and may not work so well in practice if the house is too close to adjacent houses or if the loft is full of items blocking the air flow. Alternatively, air-permeable underlays can be used, in many circumstances without any traditional ventilation, though it is important to follow the manufacturer’s installation guidance.

In roofs where the insulation is located parallel with the rafters and a vapour permeable underlay is installed in conjunction with an effective air and vapour control layer and continuous ceiling, roof space ventilation is not required. Otherwise, eaves to ridge ventilation should be installed, with clear airways in all rafter voids between the insulation and underlay.

It is worth considering when designing a building that occupants may not always use the building in the way it was intended, so err on the side of caution and provide robust solutions. For example, a family with several young children may generate far more condensation than a single person, pushing ventilation systems beyond their limits, particularly in winter.

Building Regulations and BS 5250 recognise that temporary condensation may occur during adverse climatic and internal conditions (eg, very cold outside with little or no air movement, warm indoors with no windows open). It is common to see temporary overloads of condensation appearing on the underlay, which dissipates within a few days with no harm done – usually during very cold but still weather conditions. Any temporary condensation must not be severe enough to cause damp or staining on internal surfaces or cause damage to the structure generally.

John Mercer November 2022